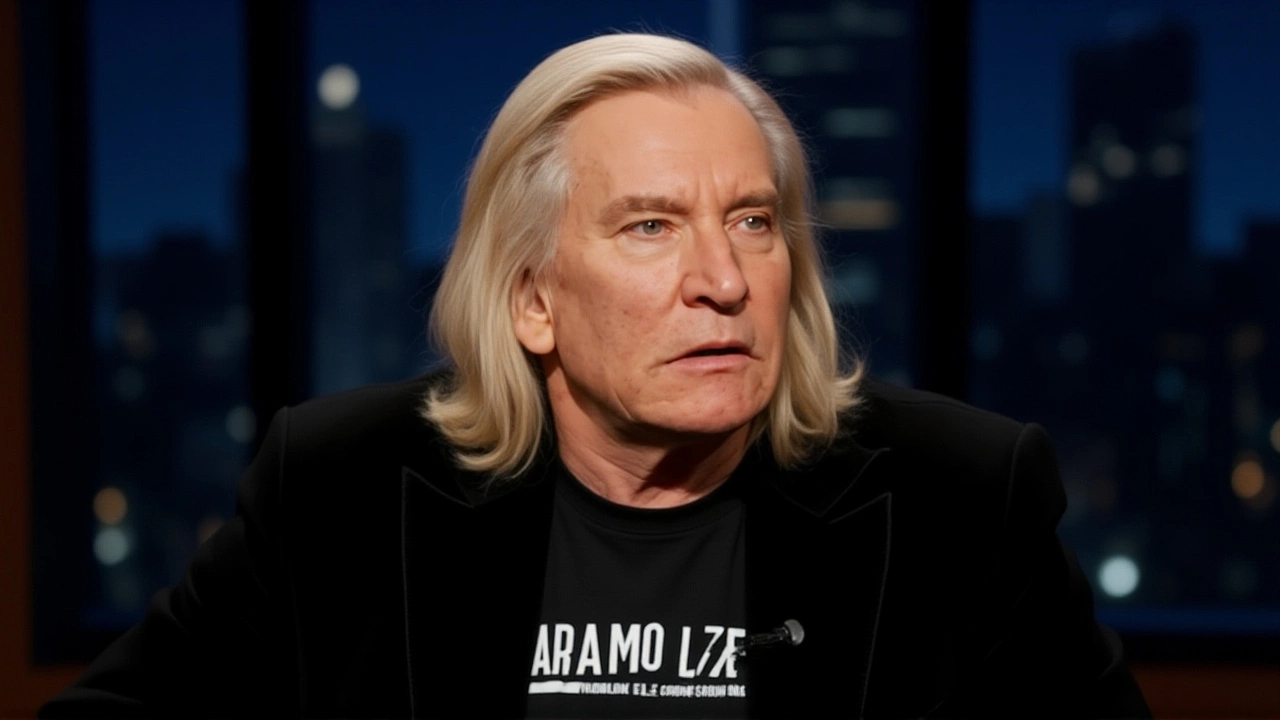

When Joe Walsh, the legendary guitarist of the Eagles, moved back to Dublin in the late 1990s, he wasn’t looking for a musical revelation. He was just home. But then he heard Whipping Boy.

That encounter didn’t just change his playlist—it rewired his brain. In a candid Q&A with journalist David Dunham, Walsh admitted: "Fuck me, that band... their album Heartworm completely changed my outlook on music. I hadn’t heard anything like it." It wasn’t just the sound. It was the words. The way they moved. The way they breathed.

The Poet Behind the Mic

Walsh didn’t just admire Whipping Boy—he idolized their singer, Fearghal. "That man was first a poet," Walsh said. "His lyrics were otherworldly to me. Poetic and undeniably Irish."

One line from Fearghal stuck with him like a tattoo: "Since when are the first line and last line of any poem where the poem begins and ends?" It wasn’t a rhetorical flourish. It was a challenge. A permission slip. Walsh had spent decades writing songs with clear verses, choruses, bridges—the classic structure. But Fearghal’s question made him wonder: What if a song didn’t need to start at the start? What if it could bleed into the listener’s life before the first note even dropped?

From Dublin to the Billboard Charts

Before Dublin, Walsh was already a rock icon. His 1978 solo hit Life’s Been Good had cracked the Top 15, a satirical anthem about rock excess wrapped in seven minutes of slide guitar and self-deprecating wit. But something shifted after Heartworm. The songs that followed—A Life of Illusion, Ordinary Average Guy—felt different. Less performative. More personal.

"If I write a song," Walsh told Dunham, "it’s because I need to say these words. I need to clear my head, to release anger, to express joy, to question the world." That’s not the voice of a man chasing radio play. That’s the voice of someone who finally understood that songs aren’t products—they’re transmissions.

That insight echoes in Life’s Been Good, which country guitarist Brad Paisley recently called "the perfect song." Paisley noted Walsh had "been writing two songs at the same time and combined them into one." That’s not just clever songcraft—it’s poetic layering. The kind of thing you learn when you’ve been listening to a poet who writes songs, not a musician who writes lyrics.

The Lineage of a Song

Walsh doesn’t believe songs belong to the artist once they’re recorded. "The saddest day of your life may inspire a song," he said, "which in turn may become someone else’s favourite song and somehow get them through their worst days. It’s the lineage, the journey of the song that makes it so special."

That’s not a cliché. It’s a philosophy. And it’s the exact opposite of the streaming-era mindset that treats music as disposable content. Walsh’s epiphany came from an Irish band that never broke America, whose album Heartworm sold maybe 20,000 copies in its first decade. Yet its influence traveled farther than any Eagles tour.

There’s a quiet irony here. One of rock’s most flamboyant guitar heroes—known for his wild stage antics, his Fender Telecaster, his laugh-out-loud lyrics about private jets and cocaine—found his deepest artistic truth in the hushed, haunting poetry of a Dublin band that never played Madison Square Garden.

What This Means for Songwriting Today

Walsh’s story isn’t just a nostalgia trip. It’s a warning. In an age where algorithms dictate structure and TikTok snippets demand 15-second hooks, the idea that a song can unfold slowly, like a poem, feels radical. Whipping Boy didn’t have a viral moment. They didn’t need one. Their power was in depth, not speed.

Walsh’s late-career evolution—his 2012 album Analog Man, his acoustic solo tours—bears the fingerprints of that Dublin awakening. The songs are longer. The silences are louder. The lyrics? Less about rock stars. More about humans.

It’s a reminder: Great art doesn’t always come from the loudest stages. Sometimes, it comes from a small club in Dublin, where a singer with a voice like worn leather asks a question no one else dared to.

Background: The Quiet Legacy of Whipping Boy

Formed in Dublin in 1990, Whipping Boy released three studio albums before disbanding in 2001. Heartworm, their 1995 sophomore record, was critically adored in Ireland but never charted outside the UK. Critics called it "a melancholy masterpiece," comparing Fearghal’s lyrics to Seamus Heaney and the early work of Patti Smith.

Walsh’s public praise in 2024 was the first time the band had received international recognition from a global rock icon. Their manager, Declan O’Rourke, told The Irish Times that the band members were "humbled, stunned, and slightly overwhelmed." Fearghal, who now teaches creative writing in Galway, said: "I never thought a man who wrote ‘Life’s Been Good’ would hear something in our songs that made him feel less alone."

That’s the quiet power of art: it doesn’t need a stage. It just needs a listener.

Frequently Asked Questions

How did Whipping Boy’s music differ from other Irish bands of the 90s?

While contemporaries like U2 or The Cranberries leaned into anthemic rock or jangle-pop, Whipping Boy embraced sparse arrangements, spoken-word delivery, and deeply personal lyrics. Their sound was closer to Nick Cave’s early work or even Leonard Cohen—minimalist, poetic, and emotionally raw. Fearghal’s lyrics avoided clichés about Irish identity, instead focusing on isolation, memory, and quiet despair, which made them feel universal.

Why did Joe Walsh’s songwriting change after hearing Heartworm?

Walsh had spent years writing songs as entertainment—catchy, punchy, often humorous. Heartworm showed him songs could be vessels for emotional truth, not just hooks. Fearghal’s nonlinear, poetic structure taught him that a song doesn’t need to resolve neatly. The discomfort, the ambiguity, the lingering questions—that’s where the real connection happens.

Has Whipping Boy reunited or released new music since Walsh’s praise?

No official reunion has occurred, and the band hasn’t released new material since 2001. However, Heartworm saw a vinyl reissue in 2023 after a surge in online interest, fueled largely by Walsh’s interviews. Streaming numbers for the album jumped 400% in the six months following his public comments.

What other artists have cited Whipping Boy as an influence?

While not widely known internationally, Irish indie artists like Lisa Hannigan, Hozier, and Fontaines D.C. have mentioned Whipping Boy in interviews as an underground touchstone. Hozier once called Heartworm "the album that taught me silence can be as loud as a guitar solo." Their influence is more subtle than overt, but it’s there—in the way modern Irish songwriters prioritize mood over melody.

How does Joe Walsh’s post-Dublin work compare to his Eagles-era material?

His Eagles-era songs like "Rocky Mountain Way" or "Life’s Been Good" are brilliant, but they’re outward-looking—telling stories about fame, excess, rebellion. After Dublin, his solo work like "The Radio Song" or "The Best of Me" turned inward. The lyrics became more introspective, the structures looser, the endings unresolved. It’s the difference between performing and confessing.

Is there a way to hear Fearghal’s original quote in context?

The full quote appears in the 1995 album liner notes for Heartworm, but it’s never been recorded as a standalone audio snippet. Walsh transcribed it from memory during his interview with Dunham. Fans have since searched through bootleg recordings of Whipping Boy’s live shows, but the exact phrasing remains elusive—adding to its mythic quality, much like a line from a lost poem.